Gameness, Aggression, and Prey Drive in Dogs

by Paul Skelton

In the following paragraphs it is my intention to delineate gameness, aggression, and prey drive in game dogs, particularly the Staffordshire Bull Terrier, American Pit Bull Terrier, and American Staffordshire Terrier with an admitted personal bias for the game bred dogs that we have bred and designed primarily for combat with each other. This does not constitute an endorsement for any activity contrary to the Animal Welfare Act of 1973 and is based upon my personal observations, experiences, and research.

I have had the distinct pleasure of knowing many breeds of dogs during my lifetime. The game breeds that I have personally been in contact with or lived with include the: American Pit Bull Terrier, Staffordshire Bull Terrier, American Staffordshire Terrier, Bull Terrier, Boston Terrier, Scottish Terrier, Jack Russell Terrier, Bulldog, American Bulldog, Black Mouthed Cur, Catahoula, Presa Canario, and Argentinean Dogo to name only some. I have also been in contact with and lived with many non-game dogs such as the Rottweiler, Pug, Cocker Spaniel, Pointer, Chow, Poodle, Dachshund, German Shepherd, Boxer, Labrador Retriever, and mutts of various lineage. Please note that Terriers are listed as game dogs. It is my contention that the difference between the Terrier and Sporting groups are the specific hunting chores they were assigned, with the major exception of the Bull and Terrier breeds previously mentioned.

The previous list is by no means complete, but provides a sample of my experience with dogs. All dog breeds can be game, aggressive and have prey drive to some extent, but the Bull and Terrier breeds have the greatest degree of gameness and thus the need for a greater understanding of its origin, use, and uniqueness.

All dogs have some form of prey drive, an instinctive reaction to chase something that moves. Its original purpose was for capturing prey as wolves, foxes, and wild dogs still do now. One of the benefits of the domestication of the dog was his instinct to chase, and thus aid in our capture of animals. Chasing a ball, flying disk, cat, or person are current examples of a dog's prey drive. What a dog does when it catches the object depends upon the training, breed of dog, and the object being chased by the dog.

I have seen a Pointer retrieve quail that were still alive with barely a feather ruffled and a Miniature Dachshund that would attempt to destroy any object that moved including golf balls and bowling balls. Many of us have seen a dog that will play fetch with a ball until all parties involved are exhausted while other dogs will only watch the toy roll away. I have seen Labradors that would retrieve until the pads on their feet were raw and bleeding, and yet would whine and cry about being taken out of the hunt. Prey drive can be related to a dog's level of desire or willingness to follow a scent or movement but is not indicative of the level of a dog's aggression or gameness.

The game dog's prey drive is usually equal to or greater than that of most hunting or herding breeds. They tend to enjoy the chase and are very attentive to anything that is running away. Their behavior upon the capture, however, has been modified less than that of other groups, in that, they still want to kill the prey rather than just locating, moving, or fetching it. My Staffords always shake their "prey" upon picking it up and will make a great show of killing it before giving it to me. This common trait survives in most dogs, but has been retained to a greater degree in game dogs. In training Retrievers and Pointers, one of the most difficult tasks is developing a "soft mouth" to prevent them from chewing or eating the prey before returning it to the hunter. I once worked with a fine Pointer that would inevitably eat the first bird retrieved. No amount of training ever got him to give up the first bird; however, he would deliver the other birds with barely a feather out of place. Prey drive is simply the manifestation of the dog's instinct to hunt for its food and has been retained or attenuated to some extent in particular breeds to meet our purposes.

Aggression in dogs, particularly aggression toward people, tends to be a learned or trained behavior. As domesticated animals, dogs have lost or repressed their instinctive fear of humans, and thus view us as their equals. We have enhanced this behavior with breeding and training programs to enhance certain dogs desire to dominate man, particularly in many of the working breeds that have been specifically developed with traits for protection against human adversaries. Aggression and its symptoms have been specifically bred out of the game dogs.

Instinctively dogs avoid hostile confrontation. In wolves, dogs direct ancestors, there are none of the typical signs of aggression when they are attacking and killing prey. The signs that we see as aggressive in dogs are usually an attempt to avoid confrontation; examples are snarling, growling, barking, raised hackles, lowered ears and a tucked tail, all generally signs that the dog wants to avoid a fight. In essence the dog is saying, "Leave me alone, I'm big and tough and you don't want to fight me, I'm the boss", or "I'm scared." all in the attempt to avoid a fight and prevent injury to himself. Within their own packs, dogs will typically defer to the higher-ranking member of the pack with submissive behaviors indicated with a wagging tail, lowered head, licking of the face, or exposure of the belly and throat. We, as dog owners, are surrogate pack members and, if properly established, even a small child will outrank a dog in the pack hierarchy and elicit these signs of submission.

In game dog breeds, aggression towards humans has been deliberately bred out. His entire purpose in life was to combat another animal, not a human being. Using the fighting dogs as an example, it would be impractical to handle a dog during the heat of battle if his attention was drawn away from his adversary to the human that was attempting to pick him up. The dog that bit a handler would be immediately killed for his transgression and would definitely not be given the opportunity to breed this trait back into the breed.

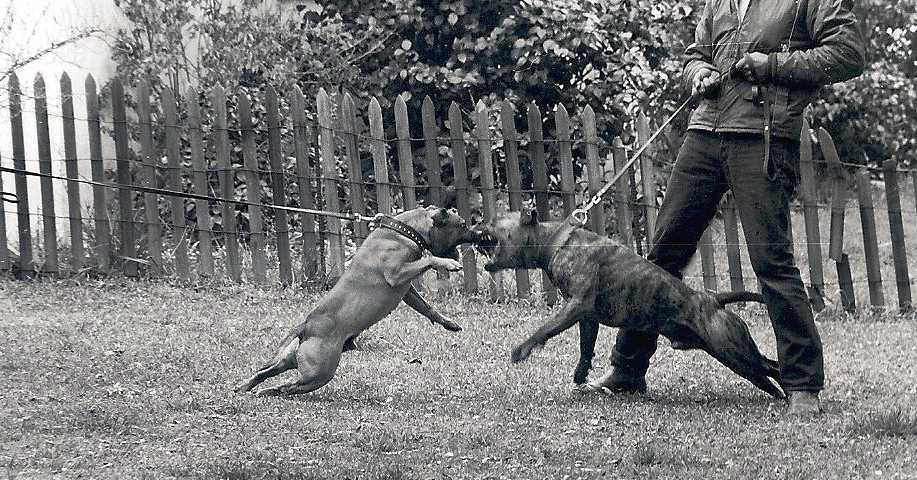

In the fighting dogs, the typical signs of aggression previously mentioned were interpreted as cowardly and were a death sentence. It may be helpful to visualize the actual, not the perceived, events in a dog match. The following description is from historical records and rules governing such matches. There are some excellent books and Internet sites that have a more complete description.

The dogs were brought to the match and washed by the opposing handler to wash away any noxious substance that may have been put on the dog that would irritate or poison its opponent. The dogs were then washed in the same water and with the same cleaner, then dried. The dogs and the handlers would enter the pit and face into the corners away from their opponent. Typically a pit was a wooden structure at least 14 feet square with a canvas flooring material and walls approximately 2-3 feet high. Approximately 2 feet from the corner would be a line marked on the canvas, "the scratch line." There would also be a line dividing the pit in half from corner to corner.

The dogs were faced and released upon the judge's command. At this point, the facing, the dogs would tend to whine, whimper, or yelp with excitement. The records indicate that there were very few indications or signs of aggression on the part of the contestants. The snarling, barking, and raised hackles that typically accompany the meeting between other breeds were not seen in truly game dogs. They wanted nothing more than to battle with each other.

(my Staffords' wrestling frightens many people. Even as puppies they enjoy scuffling and working each other. They are not being aggressive. They are simply playing a game that they both understand and enjoy.)

The dogs would meet and attempt to best their opponent. When one would get a major advantage or one would turn its head and shoulders away from his opponent, a turn would be called and the dogs would be separated for a scratch. The dog that turned or was at the disadvantage would be released while his opponent was held. The dog then typically had a ten count to get up to his opponent's scratch line and cross it. If and when one dog refused to "scratch," the contest was over. Sometimes one dog would "bolt the pit" or jump out to avoid the fight. Again the dog that bolted would be announced the loser. The contest in a dogfight was not which dog could kill the other as much as it was to see which dog would refuse to quit. It was a contest of gameness, not aggression. A dog that snarled, tucked its tail, or in any way attempted to avoid the fight was labeled a cur, typically along with its ancestors. This is not to say that dogs were never killed in the pit or died as a result of the injuries there from, but that it was not the intention of the contest. A dog that was killed or defeated, but never turned and always attempted to make scratch was considered "Dead Game" and was highly prized for his gameness if not his ability.

Thus, overall, aggression on the part of a dog is not an indication of prey drive and is the antithesis of gameness.

Gameness is a willingness to succeed or overcome, no matter what hardship must be endured. A game dog is determined to beat its opponent, no matter what odds are stacked against it, even unto death. The quality of gameness should not be confused with prey drive or aggression, in a nutshell gameness is simply the will to win. This trait cannot be taught to a dog or a man. It is an innate quality extremely difficult to reproduce in dogs, yet one of the easiest to lose. As we breed for conformation in the Bull and Terrier breeds, we should not sacrifice gameness for the sake of conformation. This invisible inherited trait makes our breeds unique. It also passes on the steadfast rock-steady temperament that has made our dogs such wonderful companions.

Gameness remains one of the most admired characteristics. The will of American fighting men to overcome hardship, adversity, and insurmountable odds has provided the freedoms that we enjoy and the successes we have achieved. In dogs, gameness shows up in their will to accomplish the tasks we assign to them. Whether it is finding a lost child in the wilderness for the Bloodhound, retrieving a downed bird in frigid water for the Retriever, making scratch with a broken stifle for the Bull and Terrier, or catching a wild boar for the American Bulldog; our faith is renewed and our admiration for "man's best friend" increases when our dogs are game enough to perform the duties for which they were bred.

Paul Skelton