Butch the Thespian

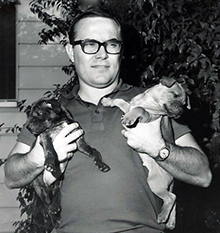

Rossisle Merely a Monarch, “Butch”. SBTC/USA Reg. No.145. By Eng. Ch. Rapparee Threapwood Handyman ex Rossisle Meddlesome Millie, showing the stump of his left hind leg which had been amputated following his attack of a garbage truck that he believed was threatening “his kids” in Birmingham, Alabama. We kept him at minimum weight to avoid stress on his hindquarters, but he was more agile on three legs than most dogs on four. Scan of a candid snapshot printed in a children's magazine.

In 1971 a family friend and fervent supporter of the Omaha Playhouse (alma mater of Henry Fonda, Dorothy MacGuire, and others) asked me to find a suitable Stafford to play Bullseye in the Playhouse production of the musical “Oliver.”

I just happened to have the ideal dog, Rossisle Merely A Monarch (Butch), whom I had just placed with a friend in Omaha. A statuesque black-brindle sired by Eng. Ch. Rapparee Threapwood Handyman ex Rossisle Meddlesome Millie, Butch had been imported by an English couple, Mr. and Mrs. Lloyd, of Birmingham, Alabama, from Rachael Swindells of Shrewsbury, England.

One day in Alabama, a garbage truck approached too close to the area where Butch was guarding his human children, and he attacked the truck. Butch lost, and one result was that his right hind leg was crushed and had to be amputated. Nevertheless, Butch became anything but a pitiable cripple, and in fact the missing leg hardly slowed him down with one outstanding exception: when he marked his territory, he had to negotiate to the left side of the objective, but on the rare occasions when he forgot to do so he would perform a handstand (frontpawstand?) to rectify the situation.

Butch had come to me because his owners were being transferred back to England and could not bear to put him through the required six months of quarantine.

I figured that a three-legged Bullseye would be the ideal cohort for the disreputable Bill Sykes, so I polished up my brass inch-wide studded Stafford collar (not much use for it in the normal course of events), and volunteered Butch's services. However, the real reason I chose Butch was that his temperament was dead-on steady, and he was the only male Stafford I've ever known personally who had the same electric, intuitive kind of intelligence that my Bella had.

Butch wearing the brass studded collar that glittered and gleamed under the stagelights, making sure that no one in the audience could miss the black brindle dog on a dim stage. The collar was strictly for theatrical performances. Scan from an old magazine.

When we first showed up at the Playhouse, I discovered that the designer had built a rather convincing if diminutive set of London Bridge, and while Butch had several appearances in other scenes, the key scene took place when Butch was to cross the dark stage, ascend a steep flight of wooden stairs, and cross London Bridge while actor Bill Bailey, talking to a Bobby on the bridge, would exclaim, “Look, there's Bill Sykes's dog!” Then the Bobby would follow Butch to Bill Sykes's door. In effect, the climax of the play hinged on Butch's performance.

I knew it would be a snap to train Butch to cross London Bridge. Maini held him while I went to the foot of the stairs. I called him, and when he came I gave him a small piece of weenie. After he returned to Maini, I ascended the stairs and called him again. Up he came like a veteran to receive another weenie bit. Back to Maini. I crossed half-way over London Bridge and called him again. He came like a homing pigeon. I then went to the far end of London Bridge, and again he came straight to me. The last stop was Bill Sykes's door near the end of London Bridge. Again Butch performed as though he had bought shares in the Playhouse.

That was the end of Butch's rehearsal. He was ready to perform.

The Director of the Playhouse and the director of Oliver had been watching Butch's progress with some trepidation, and when I notified them that Butch was ready to go, they scoffed. “Only five minutes in one rehearsal, and you say he's ready? No way!” I told them that the dog had the scene down pat and that if we rehearsed him further he would become bored. They had no option but to take my word for it.

Five days later, on Opening Night, Butch appeared onstage several times in his gleaming brass collar, on-leash at the side of actor John Dennis Johnston (who since has gone on to a solid movie career playing villains other than Bill Sykes). The dog was fascinated by the lights and by the audience, and he behaved perfectly. On cue I released him to run to and then cross London Bridge. In the darkness I could heard his claws scratching on the wooden stage, then a clump-clump as he started up the stage, then a loud thunk, then a brief silence, and then I watched Butch's shadowy form walking not across London Bridge but ACROSS STAGE to Bill Sykes's door.

Disaster! But Bill Bailey on London Bridge loudly proclaimed “I think I hear Bill Sykes's dog!” and with that quickwitted improvisation he salvaged the scene and the play without the audience tumbling to the faux pas. What actually had happened was that as Butch had clambered up the stairs, one step had fallen through, leaving Butch wedged in the resulting gap. Butch extricated himself, then scrambled down the stairs and “swam Thames River” to Bill Sykes's door!

Needless to say, the cast and crew were duly impressed with Butch's resourcefulness.

Oliver was scheduled for 27 more performances before closing at the end of the month, and never once did Butch fail to ascend the newly-reinforced stairs and cross London Bridge on cue. Bill Sykes later gave Butch in the ultimate actor's compliment, “The dog's a real trooper.”

Butch in a publicity still with actors John Johnston and Janet Seldrick at the Omaha Community Playhouse set of the musical “Oliver,” one of the greatest successes in Playhouse history. Scan from an old magazine.

An Italian proverb says, “No wonder can last for more than three days.” But in Butch's case the wonder of the audience lasted almost two weeks. While onstage he would survey the audience attentively, and during curtain calls he would literally stand at attention, trying to penetrate the veil shrouding those mysterious figures -- for, as I said, nearly two weeks.

After covering himself in theatrical glory for about 12 performances, Butch began to take notice of what was happening on stage. First he noticed that in one scene Fagan shook young Oliver vigorously and seemed to strike him, so as Fagan exited stage right past a newly-alert Butch, the dog strained mightily at the end Bill Sykes's leash, snapping his jaws at Fagan like an infuriated alligator, the clack of his teeth audible to the farthest reaches of the balcony. An alarmed Fagan appealed to the director who decided that he should should hedge his bets by exiting stage left. (The director and several members of the audience asked me how I managed to train the dog to snap his jaws like that. I assured them it was a cinch!)

Several days later Butch noticed that in one scene Bill Sykes himself shook young Oliver's shoulder, but Butch took no action at that moment. However, when Bill and Oliver were waiting offstage preparing for their next scene, Bill laid his hand on Oliver's shoulder in a encouraging gesture, but in an instant Butch leaped up and grabbed his coatsleeve.

“Oh my God,” Bill cried, “the dog bit me!”

“Are you bleeding?” I asked.

“No.”

“Do you need to go to the hospital?”

“No.”

“Then the dog didn't bite,” I told him. “He grabbed your coatsleeve to stop you from shaking the boy.” And that is precisely what did happen. Butch hadn't even perforated the coatsleeve.

Thereafter, during that scene another actor held Butch to prevent him from seeing Bill shaking young Oliver as the drama required.

The old actors' cliché about not appearing with children or dogs applied to the Playhouse production of Oliver. Everyone agreed that Butch stole the show. The actors, however, took it in good spirit.

They even invited Butch to the Cast Party!

Rossisle Merely a Monarch (Butch) and his groupies; special little friend Leslie and her friends. This is my all-time favorite Stafford photograph, taken by Jeri Marsh (copyright © Steve Stone, 1980, 1998) and typifying the essence of the true spirit of the Staffordshire Bull Terrier at home, pal and protector of his children. (detail of Butch's origins at SBTCA/USA Bulletin No. 17 last article on page.)